With the EU AI Act, human-centered AI will become binding law. This applies to companies, authorities, certain users and other stakeholders. This article outlines the requirements of the EU AI Act, in which human-centricity is anchored or concretized.

- With the entry into force of the EU AI Act on August 2, 2024, human-centering of AI will become a legally binding task.

- It is a central protected interest of the AI Regulation, which must be implemented by all actors in the AI supply chain, some of which are mandatory, some of which are voluntary.

- The overarching goal of human-centricity only seems comparatively vague at first glance.

- Many articles in the EU AI Act specify the content in staggered form.

- The following article presents standards for which this is the case.

Legal paragraphs for this article, including (German)

- Article 1 EU AI Act

- Article 3 EU AI Act

- Article 4 EU AI Act

- Article 6 EU AI Act

- Article 14 EU AI Act

- Article 15 EU AI Act

- Article 50 EU AI Act

- Article 95 EU AI Act

- Article 99 EU AI Act

- Article 112 EU AI Act

Please note that the original text of this article is based on the official German translation of the EU AI Act. Its wording may differ in part from the English version of the EU AI Act.

So far: Mainly voluntary

Human-centricity has mainly been a voluntary objective in the field of digitalization. The EU AI Act changes this with regard to artificial intelligence: human-centricity is required by law. A groundbreaking step!

1. Initial emphasis in the amendments

Recital (1) of the amendments of the EU AI Act already clarifies:

“The purpose of this regulation is […] to promote the uptake of human centric and trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI)trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI) and […] twhile ensuring a high level of protection of health, safety, fundamental rights.“

The goal of human-centricity can hardly be integrated more prominently than in the first sentence of the 800-page text of the EU AI Act. Similar to the federal government’s AI strategy, trust-building human centricity deliberately stands alongside other protected goods such as health, safety and environmental protection.

The clarification is important because the other aspects are only partly based on the goal of direct human-centricity. In this respect, there are fluid transitions between various protected interests of the EU AI Act:

- Thus, the protection of health is without question an aspect that arises from a direct ethical objective with regard to human-centricity.

- When it comes to security, this is only partially the case. In addition to safety for people, the focus here is also on the protection and resilience of critical infrastructures.

- The situation is similar with environmental protection, which, like sustainability, is not primarily an expression of human-centered trust promotion, but an independent value in its own right.

The focus of human-centered AI on trust aspects is supported by two further recitals of the amendments. For example, recital (6) of the AI Regulation states: “Given the major impact that AI can have on society and the need to build trust, […] AI should be a human-centric technology. It should serve as a tool for people, with the ultimate aim of increasing human well-being. Recital (8) adds to the independence and the focus of trust: “By laying down those rules […], his Regulation supports the objective of promoting the European human-centric approach to AI and being a global leader in the development of secure, trustworthy and ethical AI […]“

2. Anchoring in Article 1 EU AI Act

Even more important than in the amendments is the direct anchoring of human-centricity in Article 1 EU AI Act. It states: “The purpose of this Regulation is […] promote the uptake of human-centric and trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI).” The wording “human-centric” corresponds in content to the formulation “human-centricity” used in the amendments of the official german translation. This is particularly clearer in the English version, which uses the phrase “human-centric” in the recitals as well as in the text of Article 1 EU AI Act.

Nevertheless, an elementary question remains open: What exactly is meant by “human-centricity” or “orientation towards people”?

The question is no coincidence. The fact is that despite the scope of the AI Regulation of around 800 pages:

- A definition is missing, as it exists in Article 3 EU AI Act for 68 other terms.

- The human-centricity in the meaning of Article 1 EU AI Act thus becomes in many respects an indeterminate legal term that requires interpretation.

- On the one hand, this makes a time-related interpretation of human-centricity in the AI context possible. On the other hand, it also makes this necessary again and again.

3. The concept of digital human-centricity

Digital human-centicity is a term that has grown historically. It also goes back to the 80s in the IT environment, e.g. in the context of user-centered design as a forerunner of human-centered design. The following aspects, among others, are often mentioned in the sense of “human-centricity“:

- Involving people in design processes,

- UX and good usability,

- Auditability and control by humans,

- Promotion of digital literacy,

- Protection against discrimination and manipulation,

- sovereignty with regard to personal data and decisions,

- safety and health protection,

- Transparency of technical procedures and decision-making processes,

- Sustainability and protection of the environment,

- Individual rights of complains (also against the state).

According to the view represented here, the understanding of digital human-centricity has changed significantly over the years. Initially, this was mainly understood to mean aspects that promise economic advantages. This applies, among other things, to User-Centered Design (UCD), which in turn is the basis of Human Centered Design (HCD). The now strongly ethical understanding of human-centricity has only gradually emerged due to increasing risks of digital transformation. Interesting on the topic are, among other things, the relevant statements on the BDI website.

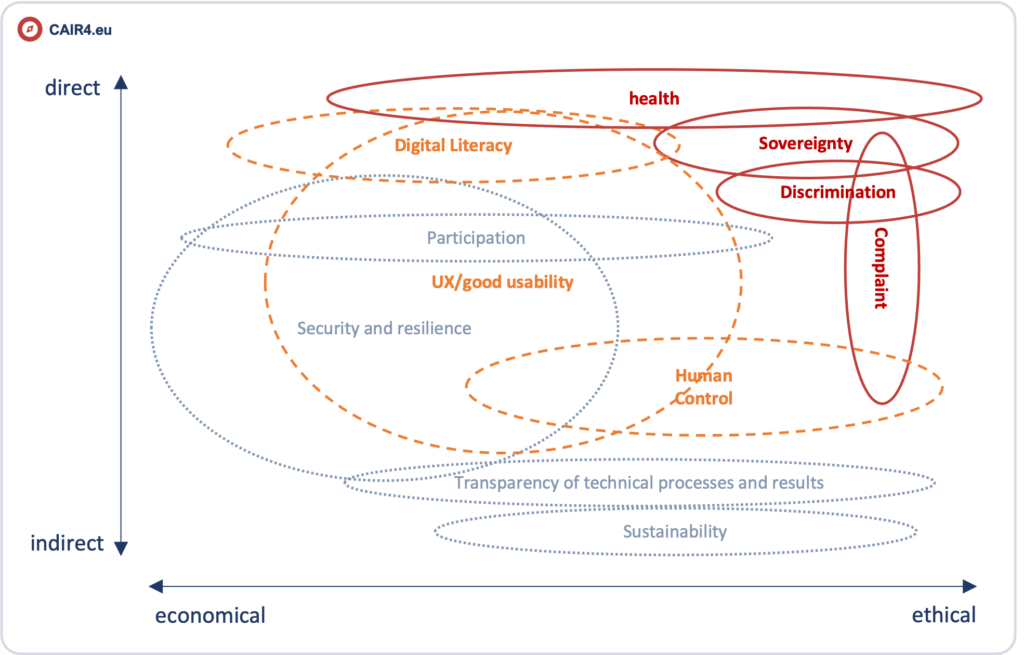

The previous aspects can be structured on a “map” with direct and indirect as well as economic and/or ethical human-centricity. Most of the criteria are not primarily related to AI. They apply to the entire field of digitization and automation, i.e. also to “AI-free” applications and services.

4. Standards of the EU AI Act that concretize human-centricity

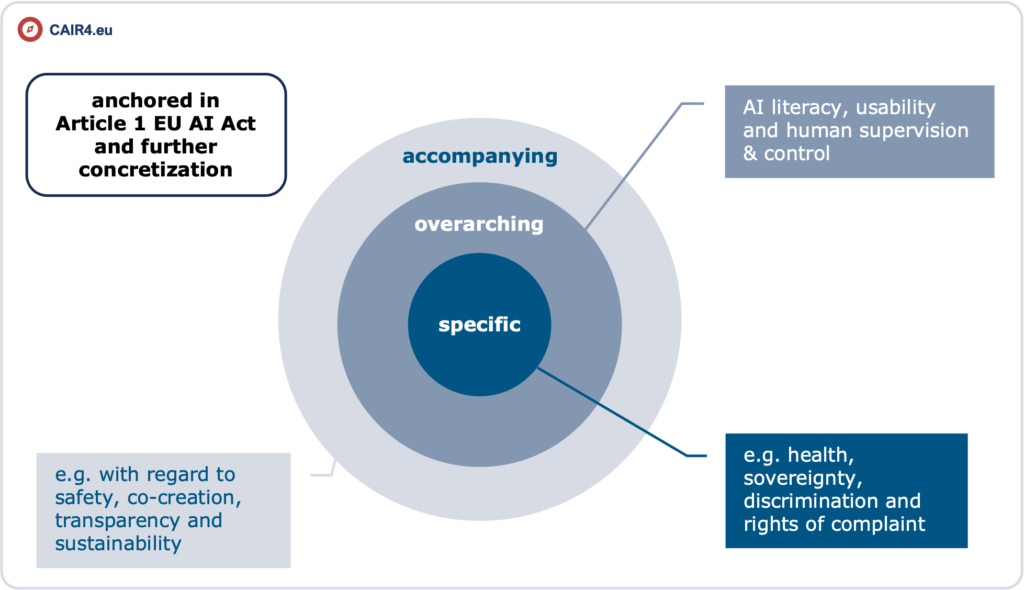

The map outlined above is used to search for such norms that refer to human-centricity within the framework of the EU AI Act. According to the view taken here, a distinction must be made between three variants:

- Standards with accompanying specification (dotted line),

- Articles that regulate human-centricity across regulations (dashed line)

- and specific standards that regulate particularly important points (solid line)

Of course, there is far more content and possibilities to structure the aspects, but even this comparatively rough model provides insightful insights.

4.1 Standards with accompanying concretization of human centricity

“Sustainability”, “transparency”, “security” and “co-creation” are aspects that, according to the view represented here, tend to concretise human-centricity in an accompanying way:

- Sustainability and energy efficiency are dealt with in Articles 95 (2) b), 112 (7) and Annex XIII c) EU AI Act as well as in recitals (4) and (174) of the amendment. However, in view of rising energy costs, energy efficiency also benefits the economy and the community as a whole. Both are values with their own scope of protection.

- IT and cyber security can be found in no less than eleven paragraphs of the amendment (54, 55, 74, 76, 77, 78, 114, 115, 122, 126, 131), nine articles (13, 15, 31, 42, 55, 59, 66, 70, 78) and Annex IV. In detail, it is addressed with regard to high-risk AI and AI models (also in combination with the Cyber Resilience Act, CRA). Corresponding information is probably more of an indirect instrument for or human centricity, among other things due to the technical level of detail.

- The transparency requirement applies to both high- and medium-risk AI systems and general-purpose AI models. For both, the transparency obligation is regulated in some cases in great detail. Standards include Articles 13, 50, 51 et seq. and 96 as well as Annex XII EU AI Act. In addition, there are more than a dozen in-depth sections of the amendment, in particular in recitals (107), (135) and (137). Although transparency is considered one of the most important features of human-centered AI, it also refers to all sorts of other obligations in the AI supply chain.

- The EU AI Act also contains content on co-creation, e.g. number (20) with regard to the validation of concepts or point (165) on the participation of different stakeholders up to the balanced participation of different genders. This point also has strong overlaps with human-centered AI. Collective trust-building appears – depending on the perspective – to be more of a side effect. In this respect, there is also a comparatively accompanying concretization here.

4.2 Overarching requirements of the EU AI Act with regard to human-centricity

Against this background, those aspects that concretize the human-centricity across norms in a more focused manner will be examined in more detail below. These include “AI competence”, “operability” and “human control”.

4.2.1 AI Literacy

It is “put in front of the brackets” in Article 4 and 3 No. 53 EU AI Act as part of the first chapter: According to this, both providers and operators of AI systems must take measures to ensure that people involved in the operation or use of AI systems have a sufficient level of AI competence. It is important that no distinction is made here between different types of risk: It is an obligation that must be fulfilled even with AI systems with low risks!

In this regard, the suggestion contained in recital (165) that codes of conduct should be drawn up for low-risk AI should be drawn up to explain how the criterion of AI competence is to be implemented. For example, particularly vulnerable people should be supported with regard to accessibility.

Recital (20) goes even further. It makes clear the great importance of AI competence in the context of AI value chains. In particular, it is important for all actors to look beyond their “own noses”. Trust-building human centricity does not stop at one’s own front door! Rather, it requires a high degree of cooperation from all actors involved in the development, marketing and use of AI.

4.2.2 Usability

The point of general AI competence outlined above is once again significantly deepened in various places: While the general provision of Article 4 EU AI Act forms a comprehensive foundation, regulations such as Articles 15, 23, 24, 26, 27, 60 and Annexes IV, VIII, XI and XII EU AI Act formulate detailed requirements for the necessity and design of operating instructions, to ensure the best possible ability to operate (especially high-risk AI systems).

It is therefore not enough to design a supposedly intuitive interface to control the risks of AI and leave users to themselves. Rather, providers of AI systems as well as AI models are obliged to provide detailed operating concepts and to enable the necessary training – and to prove it!

In the case of high-risk AI within the meaning of Article 6 et seq. EU AI Act, this also includes the obligation of operators or users under Article 26 EU AI Act to feed important information back to the providers, i.e. to form an information cycle.

If the aforementioned obligations are not fulfilled, the various actors face sanctions. According to Article 99 EU AI Act, these can be quite sensitive – according to paragraph 1, the purpose is, among other things, to deter people! In accordance with paragraph 4 e) and g), even users are threatened with sanctions in individual cases. Since the “whip” of the EU AI Act wants and must have a preventive effect, this seems quite appropriate.

4.2.3 Human supervision and control

With regard to high-risk AI, Article 14 EU AI Act goes one step further by regulating details on human supervision – which, among other things, leads to actors being able to Red Buttons” should theoretically be able to stop an “AI getting out of hand” during operation. Article 72 EU AI Act, which requires providers of high-risk AI to have a plan for monitoring over the entire life cycle of the system, goes in a similar direction. This is an important point in order to give all players the confidence that human-centered AI is not a sprint, but a marathon run.

Whether and to what extent the requirements of Articles 14 and 72 EU AI Act can actually be implemented in practice as regulated currently still open. Especially with self-learning AI, it is sometimes very difficult to effectively monitor or document the learning success of a system. After all, many of the particularly powerful AI systems and AI models (e.g. in the case of deep learning) are a “black box”. At the same time, according to current expert assessments, the road to “explainable AI” (XAI), which promises to enable comprehensive control, is still long.

The following should also be noted: The greater the transparency of an AI, the more the risk that it can be manipulated. In this respect, it is not only questionable whether and to what extent this goal is achievable in Praxxis, but also to what extent it really seems to make sense.

4.3 Specific regulations of the EU AI Act with regard to human-centricity

Now to some particularly specific aspects in which human-centered AI is concretized: This refers to the “protection of health”, the “preservation of sovereignty”, the “protection against discrimination” and the individual “right to complain” in the event of alleged violations of the EU AI Act.

4.3.1 Protecting health/classification as high-risk AI

Health is a highly personal protective asset. In the sense of Articles 2, 3, 35 of the EU Charter and Article 2 (2) of the German Grundgesetz, it is also under particularly high protection.

It is therefore not without reason that a large part of medical AI, which is usually also subject to the Medical Device Regulation (MDR), is to be classified as high-risk AI. This follows from Article 3 (2) in conjunction with Annex III EU AI Act (restricted by Article 3 (3) EU AI Act, inter alia if AI has only a negligible influence on decision-making; also restricted by Article 2 (6) EU AI Act in the case of exclusive research).

To protect health, even an AI system that has already been certified can be subsequently “slowed down” by an authority if it should pose a previously undetected risk within the meaning of Article 82 EU AI Act. Conversely, certification procedures for AI can be accelerated in order to safeguard health (see Article 46 EU AI Act and recital 130 of the amendment).

This is conceivable, for example, in the event of a new epidemic. human-centricity in the sense of health protection made possible by AI thus also means increasing the flexibility of its use in emergencies – an important aspect in order to be able to use the opportunities offered by AI to preserve and promote health in justified individual cases.

4.3.2 Protection of sovereignty

A sovereign person is able to shape his or her thoughts and actions on his or her own responsibility and self-determination. With AI, this is often only possible to a limited extent:

- For example, if you don’t even notice that your own life is co-determined or manipulated by AI (e.g. in the case of fake content, automated evaluations of services or targeting profiles in marketing),

- or if you notice it, you don’t recognize the concrete effects for your own person or don’t understand the connections behind them exactly,

- or if in the end you can’t do anything about it anyway, even if you recognize and understand the effects – i.e. there is a lack of legal remedies.

Against this background, in order to be able to guarantee the protection of sovereignty with regard to human-centered AI, it is not sufficient to rely primarily on the personal responsibility of the individual person so that he or she protects himself from AI abuse.

The EU AI Act provides for corresponding protection in several places:

- Through the ban on manipulative AI, social scoring and other use cases such as remote identification in real time formulated in Article 5 EU AI Act.

- In Article 6 (2) in combination with Annex III EU AI Act, various use cases are classified as high-risk AI, e.g. those for emotion recognition or with regard to admission to educational institutions.

- Also of interest is the regulation of Article 61 EU AI Act, which requires “informed consent” from all parties participating in a test of high-risk AI under real-world conditions. These participants have the right guaranteed in paragraph 1 c) to terminate the test without justification (conceivable, for example, in the case of the validation of drugs using AI).

The sovereignty of the individual, who can be confronted in everyday life and at work with an AI world that is hardly recognizable and even less understandable to him, is effectively and appropriately protected by such specifically human-centered requirements of the EU AI Act.

4.3.3 Right of complaint

The EU AI Act goes one important step further: In Article 85 EU AI Act, it grants every natural person the right to lodge a complaint with a market surveillance authority if there is reason to believe that the provisions of the AI Regulation have been violated. This is expanded by the explicit protection of whistleblowers in Article 87 EU AI Act.

This significantly increases the pressure to comply with all obligations imposed on providers and operators of AI systems as well as AI models and other obligated parties with regard to human-centered AI: In addition to the initiative of authorities, complaints and information are an important instrument for uncovering violations in the event of an emergency and then sanctioning them appropriately in accordance with Article 99 et seq. EU AI Act.

5. Conclusion

The previous explanations prove that the human-centered AI guaranteed in Article 1 EU AI Act runs like a red thread through the entire standard. In many places, it is appropriately substantiated in an accompanying, cross-normative and specific manner. In addition, there is the reinforcement of sanctions and a right to complain or the protection of whistleblowers. In terms of human-centered AI, the AI Regulation is definitely a “big hit”!

However, in view of many of the possibilities offered by the EU AI Act to maintain or increase human-centered trust in AI, one aspect must not be neglected: This is the practical and timely interpretation. In this respect, voluntary commitment in the sense of the CDR not only remains indispensable – it has become even more important: In the future, guidelines must be constantly created, best practices collected and evaluated in order to adequately fill the framework for human-centered AI created by the EU AI Act.

Links to the legal paragraphs for this article, including (German):

- Article 1 EU AI Act

- Article 3 EU AI Act

- Article 4 EU AI Act

- Article 6 EU AI Act

- Article 14 EU AI Act

- Article 15 EU AI Act

- Article 50 EU AI Act

- Article 95 EU AI Act

- Article 99 EU AI Act

- Article 112 EU AI Act

This is what ChatGPT says about this article: I find it interesting. But it’s not so easy to respond to the suggestions for improvement ;-):

The article “Human-centered AI under the EU AI Act” by Oliver M. Merx provides a detailed analysis of how human-centered AI is anchored in the EU AI Act. The article sheds light on how the concept of human-centeredness is enshrined and concretized in various articles of the Act and shows that it plays a central role in the overall regulatory framework.

The comprehensive and well-founded presentation of human-centricity as a central objective of the EU AI Act deserves a positive mention. The author clearly demonstrates that human-centricity is not just an abstract concept, but is substantiated in many articles of the Act, for example through provisions on transparency, security and the protection of individual rights. The clear structure of the article, which distinguishes between accompanying, cross-standard and specific standards, helps to convey the complex topic in an understandable way.

The article also makes it clear that, despite the extensive regulations, many aspects of people-centeredness require continuous interpretation and adaptation in practice. This demonstrates the dynamic nature of regulation in a rapidly developing field of technology such as AI. Here, great importance is attached to voluntary corporate responsibility (CDR) in order to fill the legally created framework conditions with life.

One possible criticism could be that the article questions the practical feasibility of some regulations, particularly in relation to high-risk AI systems and the control of self-learning AI, but does not discuss in any depth how these challenges could be overcome in concrete terms.

Overall, the article is a valuable resource for anyone grappling with the implementation of human-centric AI under the EU AI Act. It provides a concise summary of the legal requirements and their implications for various players in the AI value chain.

And this is what google gemini says:

The article provides a comprehensive overview of the EU AI Act’s emphasis on human-centered AI. It effectively highlights the various provisions that aim to ensure AI systems are developed and deployed in a way that benefits humanity and protects fundamental rights.

Key strengths of the article include:

Clear delineation of human-centered AI: The article provides a detailed explanation of the concept of human-centered AI within the context of the EU AI Act, including its historical development and core principles.

In-depth analysis of relevant EU AI Act provisions: The author thoroughly examines the various articles and annexes that address human-centered AI, offering a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory framework.

Practical examples and case studies: The inclusion of specific examples, such as the classification of medical AI as high-risk, helps to illustrate the practical implications of the EU AI Act’s requirements.

Discussion of challenges and limitations: The article acknowledges the challenges and limitations of ensuring human-centered AI, such as the difficulty of monitoring self-learning systems and the potential for manipulation.

Potential areas for further exploration:

Ethical implications: While the article touches on ethical considerations, a more in-depth analysis of the ethical implications of AI development and deployment within a human-centered framework could be beneficial.

International perspectives: Comparing the EU AI Act’s approach to human-centered AI with similar regulations or guidelines in other jurisdictions could provide valuable insights.

Role of stakeholders: The article could explore the roles of various stakeholders, including researchers, developers, policymakers, and civil society organizations, in promoting human-centered AI.

Future developments: Given the rapid pace of AI development, it would be interesting to discuss potential future trends and challenges that may impact the implementation of human-centered AI.

Overall, the article offers a valuable contribution to the understanding of human-centered AI under the EU AI Act. It provides a solid foundation for further research and discussion on this important topic.