Folgende Verweise sind für diesen Artikel relevant: Artikel 5, 6, 10, 50, 57, 59, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 112 EU AI Act

Artikel 5

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

VERBOTENE PRAKTIKEN IM KI-BEREICH

(1) Folgende Praktiken im KI-Bereich sind verboten:

a) das Inverkehrbringen, die Inbetriebnahme oder die Verwendung eines KI-Systems, das Techniken der unterschwelligen Beeinflussung außerhalb des Bewusstseins einer Person oder absichtlich manipulative oder täuschende Techniken mit dem Ziel oder der Wirkung einsetzt, das Verhalten einer Person oder einer Gruppe von Personen wesentlich zu verändern, indem ihre Fähigkeit, eine fundierte Entscheidung zu treffen, deutlich beeinträchtigt wird, wodurch sie veranlasst wird, eine Entscheidung zu treffen, die sie andernfalls nicht getroffen hätte, und zwar in einer Weise, die dieser Person, einer anderen Person oder einer Gruppe von Personen erheblichen Schaden zufügt oder mit hinreichender Wahrscheinlichkeit zufügen wird.

b) das Inverkehrbringen, die Inbetriebnahme oder die Verwendung eines KI-Systems, das eine Vulnerabilität oder Schutzbedürftigkeit einer natürlichen Person oder einer bestimmten Gruppe von Personen aufgrund ihres Alters, einer Behinderung oder einer bestimmten sozialen oder wirtschaftlichen Situation mit dem Ziel oder der Wirkung ausnutzt, das Verhalten dieser Person oder einer dieser Gruppe angehörenden Person in einer Weise wesentlich zu verändern, die dieser Person oder einer anderen Person erheblichen Schaden zufügt oder mit hinreichender Wahrscheinlichkeit zufügen wird;

c) das Inverkehrbringen, die Inbetriebnahme oder die Verwendung von KI-Systemen zur Bewertung oder Einstufung von natürlichen Personen oder Gruppen von Personen über einen bestimmten Zeitraum auf der Grundlage ihres sozialen Verhaltens oder bekannter, abgeleiteter oder vorhergesagter persönlicher Eigenschaften oder Persönlichkeitsmerkmale, wobei die soziale Bewertung zu einem oder beiden der folgenden Ergebnisse führt:

i) Schlechtersellung oder Benachteiligung bestimmter natürlicher Personen oder Gruppen von Personen in sozialen Zusammenhängen, die in keinem Zusammenhang zu den Umständen stehen, unter denen die Daten ursprünglich erzeugt oder erhoben wurden;

ii) Schlechterstellung oder Benachteiligung bestimmter natürlicher Personen oder Gruppen von Personen in einer Weise, die im Hinblick auf ihr soziales Verhalten oder dessen Tragweite ungerechtfertigt oder unverhältnismäßig ist;

(d) das Inverkehrbringen, die Inbetriebnahme zu diesem speziellen Zweck oder die Verwendung eines KI-Systems für Risikobewertungen natürlicher Personen, um das Risiko, dass eine natürliche Person eine Straftat begeht, zu bewerten oder vorherzusagen, und zwar ausschließlich auf der Grundlage der Erstellung eines Profils einer natürlichen Person oder der Bewertung ihrer Persönlichkeitsmerkmale und Eigenschaften; dieses Verbot gilt nicht für KI-Systeme, die zur Unterstützung der menschlichen Bewertung der Beteiligung einer Person an einer kriminellen Tätigkeit verwendet werden, die bereits auf objektiven und überprüfbaren Tatsachen beruht, die in direktem Zusammenhang mit einer kriminellen Tätigkeit stehen;

(e) das Inverkehrbringen, die Inbetriebnahme zu diesem speziellen Zweck oder die Verwendung von KI-Systemen, die Datenbanken für die Gesichtserkennung durch das ungezielte Auslesen von Gesichtsbildern aus dem Internet oder aus Videoüberwachungsaufnahmen erstellen oder erweitern;

(f) das Inverkehrbringen, die Inbetriebnahme zu diesem speziellen Zweck oder die Verwendung von KI-Systemen zur Ableitung von Emotionen einer natürlichen Person in den Bereichen Arbeitsplatz und Bildungseinrichtungen, es sei denn, die Verwendung des KI-Systems soll aus medizinischen oder sicherheitstechnischen Gründen eingeführt oder in Verkehr gebracht werden

(g) das Inverkehrbringen, die Inbetriebnahme zu diesem speziellen Zweck oder die Verwendung biometrischer Kategorisierungssysteme, die einzelne natürliche Personen auf der Grundlage ihrer biometrischen Daten kategorisieren, um Rückschlüsse auf ihre Ethnie, ihre politischen Meinungen, ihre Gewerkschaftszugehörigkeit, ihre religiösen oder philosophischen Überzeugungen, ihr Sexualleben oder ihre sexuelle Ausrichtung zu ziehen; dieses Verbot erstreckt sich nicht auf die Kennzeichnung oder Filterung rechtmäßig erworbener biometrischer Datensätze, wie z. B. Bilder, auf der Grundlage biometrischer Daten oder auf die Kategorisierung biometrischer Daten im Bereich der Strafverfolgung

(h) die Verwendung von biometrischen Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssystemen in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Zwecken der Strafverfolgung, es sei denn, eine solche Verwendung ist für eines der folgenden Ziele unbedingt erforderlich:

(i) die gezielte Suche nach bestimmten Opfern von Entführung, Menschenhandel oder sexueller Ausbeutung von Menschen sowie die Suche nach vermissten Personen;

(ii) die Abwehr einer konkreten, erheblichen und unmittelbaren Gefahr für das Leben oder die körperliche Sicherheit natürlicher Personen oder einer tatsächlichen und gegenwärtigen oder tatsächlichen und vorhersehbaren Gefahr eines Terroranschlags;

(iii) die Lokalisierung oder Identifizierung einer Person, die im Verdacht steht, eine Straftat begangen zu haben, zum Zwecke der Durchführung strafrechtlicher Ermittlungen oder der Strafverfolgung oder der Vollstreckung einer strafrechtlichen Sanktion für Straftaten nach Anhang II, die in dem betreffenden Mitgliedstaat mit einer Freiheitsstrafe oder einer freiheitsentziehenden Maßregel der Sicherung im Höchstmaß von mindestens vier Jahren bedroht sind. Unterabsatz 1 Buchstabe h gilt unbeschadet des Artikels 9 der Verordnung (EU) 2016/679 für die Verarbeitung biometrischer Daten zu anderen als Strafverfolgungszwecken.

(2) Die Verwendung biometrischer Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssysteme in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Strafverfolgungszwecken im Hinblick auf die in Absatz 1 Unterabsatz 1 Buchstabe h genannten Ziele darf für die in jenem Buchstaben genannten Zwecke nur zur Bestätigung der Identität der speziell betroffenen Person erfolgen, wobei folgende Elemente berücksichtigt werden:

a) die Art der Situation, die der möglichen Verwendung zugrunde liegt, insbesondere die Schwere, die Wahrscheinlichkeit und das Ausmaß des Schadens, der entstehen würde, wenn das System nicht eingesetzt würde;

b) die Folgen der Verwendung des Systems für die Rechte und Freiheiten aller betroffenen Personen, insbesondere die Schwere, die Wahrscheinlichkeit und das Ausmaß solcher Folgen.

Darüber hinaus sind bei der Verwendung biometrischer Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssysteme in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Strafverfolgungszwecken im Hinblick auf die in Absatz 1 Unterabsatz 1 Buchstabe h des vorliegenden Artikels genannten Ziele notwendige und verhältnismäßige Schutzvorkehrungen und Bedingungen für die Verwendung im Einklang mit nationalem Recht über die Ermächtigung ihrer Verwendung einzuhalten, insbesondere in Bezug auf die zeitlichen, geografischen und personenbezogenen Beschränkungen. Die Verwendung biometrischer Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssysteme in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen ist nur dann zu gestatten, wenn die Strafverfolgungsbehörde eine Folgenabschätzung im Hinblick auf die Grundrechte gemäß Artikel 27 abgeschlossen und das System gemäß Artikel 49 in der EU-Datenbank registriert hat. In hinreichend begründeten dringenden Fällen kann jedoch mit der Verwendung solcher Systeme zunächst ohne Registrierung in der EU-Datenbank begonnen werden, sofern diese Registrierung unverzüglich erfolgt.

(3) Für die Zwecke des Absatz 1 Unterabsatz 1 Buchstabe h und des Absatzes 2 ist für jede Verwendung eines biometrischen Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssystems in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Strafverfolgungszwecken eine vorherige Genehmigung erforderlich, die von einer Justizbehörde oder einer unabhängigen Verwaltungsbehörde des Mitgliedstaats, in dem die Verwendung erfolgen soll, auf begründeten Antrag und gemäß den in Absatz 5 genannten detaillierten nationalen Rechtsvorschriften erteilt wird, wobei deren Entscheidung bindend ist. In hinreichend begründeten dringenden Fällen kann jedoch mit der Verwendung eines solchen Systems zunächst ohne Genehmigung begonnen werden, sofern eine solche Genehmigung unverzüglich, spätestens jedoch innerhalb von 24 Stunden beantragt wird. Wird eine solche Genehmigung abgelehnt, so wird die Verwendung mit sofortiger Wirkung eingestellt und werden alle Daten sowie die Ergebnisse und Ausgaben dieser Verwendung unverzüglich verworfen und gelöscht.

Die zuständige Justizbehörde oder eine unabhängige Verwaltungsbehörde, deren Entscheidung bindend ist, erteilt die Genehmigung nur dann, wenn sie auf der Grundlage objektiver Nachweise oder eindeutiger Hinweise, die ihr vorgelegt werden, davon überzeugt ist, dass die Verwendung des betreffenden biometrischen Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssystems für das Erreichen eines der in Absatz 1 Unterabsatz 1 Buchstabe h genannten Ziele — wie im Antrag angegeben — notwendig und verhältnismäßig ist und insbesondere auf das in Bezug auf den Zeitraum sowie den geografischen und persönlichen Anwendungsbereich unbedingt erforderliche Maß beschränkt bleibt. Bei ihrer Entscheidung über den Antrag berücksichtigt diese Behörde die in Absatz 2 genannten Elemente. Eine Entscheidung, aus der sich eine nachteilige Rechtsfolge für eine Person ergibt, darf nicht ausschließlich auf der Grundlage der Ausgabe des biometrischen Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssystems getroffen werden.

(4) Unbeschadet des Absatzes 3 wird jede Verwendung eines biometrischen Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssystems in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Strafverfolgungszwecken der zuständigen Marktüberwachungsbehörde und der nationalen Datenschutzbehörde gemäß den in Absatz 5 genannten nationalen Vorschriften mitgeteilt. Die Mitteilung muss mindestens die in Absatz 6 genannten Angaben enthalten und darf keine sensiblen operativen Daten enthalten.

(5) Ein Mitgliedstaat kann die Möglichkeit einer vollständigen oder teilweisen Ermächtigung zur Verwendung biometrischer Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssysteme in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Strafverfolgungszwecken innerhalb der in Absatz 1 Unterabsatz 1 Buchstabe h sowie Absätze 2 und 3 aufgeführten Grenzen und unter den dort genannten Bedingungen vorsehen. Die betreffenden Mitgliedstaaten legen in ihrem nationalen Recht die erforderlichen detaillierten Vorschriften für die Beantragung, Erteilung und Ausübung der in Absatz 3 genannten Genehmigungen sowie für die entsprechende Beaufsichtigung und Berichterstattung fest. In diesen Vorschriften wird auch festgelegt, im Hinblick auf welche der in Absatz 1 Unterabsatz 1 Buchstabe h aufgeführten Ziele und welche der unter Buchstabe h Ziffer iii genannten Straftaten die zuständigen Behörden ermächtigt werden können, diese Systeme zu Strafverfolgungszwecken zu verwenden. Die Mitgliedstaaten teilen der Kommission diese Vorschriften spätestens 30 Tage nach ihrem Erlass mit. Die Mitgliedstaaten können im Einklang mit dem Unionsrecht strengere Rechtsvorschriften für die Verwendung biometrischer Fernidentifizierungssysteme erlassen.

(6) Die nationalen Marktüberwachungsbehörden und die nationalen Datenschutzbehörden der Mitgliedstaaten, denen gemäß Absatz 4 die Verwendung biometrischer Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssysteme in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Strafverfolgungszwecken mitgeteilt wurden, legen der Kommission Jahresberichte über diese Verwendung vor. Zu diesem Zweck stellt die Kommission den Mitgliedstaaten und den nationalen Marktüberwachungs- und Datenschutzbehörden ein Muster zur Verfügung, das Angaben über die Anzahl der Entscheidungen der zuständigen Justizbehörden oder einer unabhängigen Verwaltungsbehörde, deren Entscheidung über Genehmigungsanträge gemäß Absatz 3 bindend ist, und deren Ergebnis enthält.

(7) Die Kommission veröffentlicht Jahresberichte über die Verwendung biometrischer Echtzeit-Fernidentifizierungssysteme in öffentlich zugänglichen Räumen zu Strafverfolgungszwecken, die auf aggregierten Daten aus den Mitgliedstaaten auf der Grundlage der in Absatz 6 genannten Jahresberichte beruhen. Diese Jahresberichte dürfen keine sensiblen operativen Daten im Zusammenhang mit den damit verbundenen Strafverfolgungsmaßnahmen enthalten.

(8) Dieser Artikel berührt nicht die Verbote, die gelten, wenn KI-Praktiken gegen andere Rechtsvorschriften der Union verstoßen.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 6

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Einstufungsvorschriften für Hochrisiko-KI-Systeme

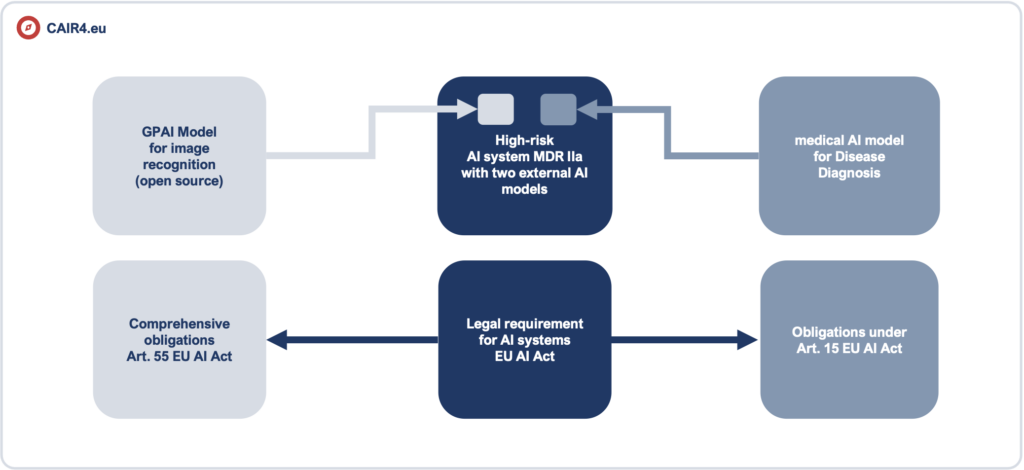

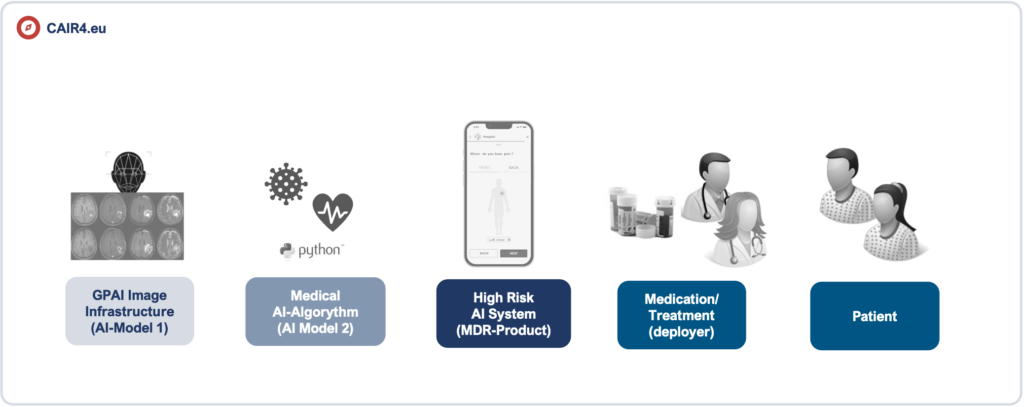

(1) Ungeachtet dessen, ob ein KI-System unabhängig von den unter den Buchstaben a und b genannten Produkten in Verkehr gebracht oder in Betrieb genommen wird, gilt es als Hochrisiko-KI-System, wenn die beiden folgenden Bedingungen erfüllt sind:

a) das KI-System soll als Sicherheitsbauteil eines unter die in Anhang I aufgeführten Harmonisierungsrechtsvorschriften der Union fallenden Produkts verwendet werden oder das KI-System ist selbst ein solches Produkt;

b) das Produkt, dessen Sicherheitsbauteil gemäß Buchstabe a das KI-System ist, oder das KI-System selbst als Produkt muss einer Konformitätsbewertung durch Dritte im Hinblick auf das Inverkehrbringen oder die Inbetriebnahme dieses Produkts gemäß den in Anhang I aufgeführten Harmonisierungsrechtsvorschriften der Union unterzogen werden.

(2) Zusätzlich zu den in Absatz 1 genannten Hochrisiko-KI-Systemen gelten die in Anhang III genannten KI-Systeme als hochriskant.

(3) Abweichend von Absatz 2 gilt ein in Anhang III genanntes KI-System nicht als hochriskant, wenn es kein erhebliches Risiko der Beeinträchtigung in Bezug auf die Gesundheit, Sicherheit oder Grundrechte natürlicher Personen birgt, indem es unter anderem nicht das Ergebnis der Entscheidungsfindung wesentlich beeinflusst.

Unterabsatz 1 gilt, wenn eine der folgenden Bedingungen erfüllt ist:

a) das KI-System ist dazu bestimmt, eine eng gefasste Verfahrensaufgabe durchzuführen;

b) das KI-System ist dazu bestimmt, das Ergebnis einer zuvor abgeschlossenen menschlichen Tätigkeit zu verbessern;

c) das KI-System ist dazu bestimmt, Entscheidungsmuster oder Abweichungen von früheren Entscheidungsmustern zu erkennen, und ist nicht dazu gedacht, die zuvor abgeschlossene menschliche Bewertung ohne eine angemessene menschliche Überprüfung zu ersetzen oder zu beeinflussen; oder

d) das KI-System ist dazu bestimmt, eine vorbereitende Aufgabe für eine Bewertung durchzuführen, die für die Zwecke der in Anhang III aufgeführten Anwendungsfälle relevant ist.

Ungeachtet des Unterabsatzes 1 gilt ein in Anhang III aufgeführtes KI-System immer dann als hochriskant, wenn es ein Profiling natürlicher Personen vornimmt.

(4) Ein Anbieter, der der Auffassung ist, dass ein in Anhang III aufgeführtes KI-System nicht hochriskant ist, dokumentiert seine Bewertung, bevor dieses System in Verkehr gebracht oder in Betrieb genommen wird. Dieser Anbieter unterliegt der Registrierungspflicht gemäß Artikel 49 Absatz 2. Auf Verlangen der zuständigen nationalen Behörden legt der Anbieter die Dokumentation der Bewertung vor.

(5) Die Kommission stellt nach Konsultation des Europäischen Gremiums für Künstliche Intelligenz (im Folgenden „KI-Gremium“) spätestens bis zum 2. Februar 2026 Leitlinien zur praktischen Umsetzung dieses Artikels gemäß Artikel 96 und eine umfassende Liste praktischer Beispiele für Anwendungsfälle für KI-Systeme, die hochriskant oder nicht hochriskant sind, bereit.

(6) Die Kommission ist befugt, gemäß Artikel 97 delegierte Rechtsakte zu erlassen, um Absatz 3 Unterabsatz 2 des vorliegenden Artikels zu ändern, indem neue Bedingungen zu den darin genannten Bedingungen hinzugefügt oder diese geändert werden, wenn konkrete und zuverlässige Beweise für das Vorhandensein von KI-Systemen vorliegen, die in den Anwendungsbereich von Anhang III fallen, jedoch kein erhebliches Risiko der Beeinträchtigung in Bezug auf die Gesundheit, Sicherheit oder Grundrechte natürlicher Personen bergen.

(7) Die Kommission erlässt gemäß Artikel 97 delegierte Rechtsakte, um Absatz 3 Unterabsatz 2 des vorliegenden Artikels zu ändern, indem eine der darin festgelegten Bedingungen gestrichen wird, wenn konkrete und zuverlässige Beweise dafür vorliegen, dass dies für die Aufrechterhaltung des Schutzniveaus in Bezug auf Gesundheit, Sicherheit und die in dieser Verordnung vorgesehenen Grundrechte erforderlich ist.

(8) Eine Änderung der in Absatz 3 Unterabsatz 2 festgelegten Bedingungen, die gemäß den Absätzen 6 und 7 des vorliegenden Artikels erlassen wurde, darf das allgemeine Schutzniveau in Bezug auf Gesundheit, Sicherheit und die in dieser Verordnung vorgesehenen Grundrechte nicht senken; dabei ist die Kohärenz mit den gemäß Artikel 7 Absatz 1 erlassenen delegierten Rechtsakten sicherzustellen und die Marktentwicklungen und die technologischen Entwicklungen sind zu berücksichtigen.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 10

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Daten and Daten Governance

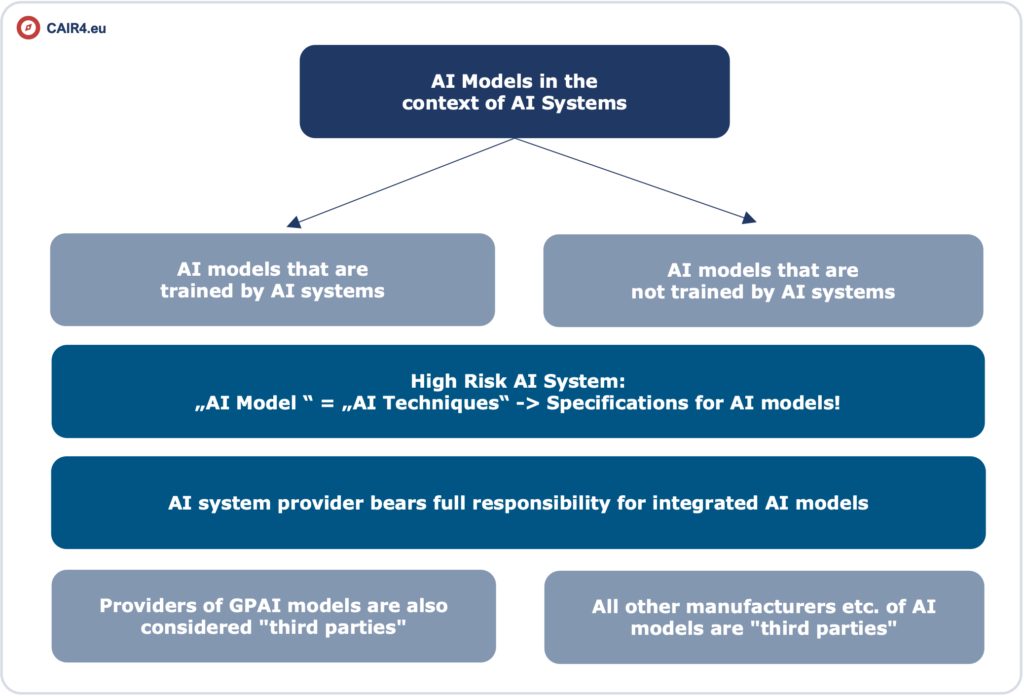

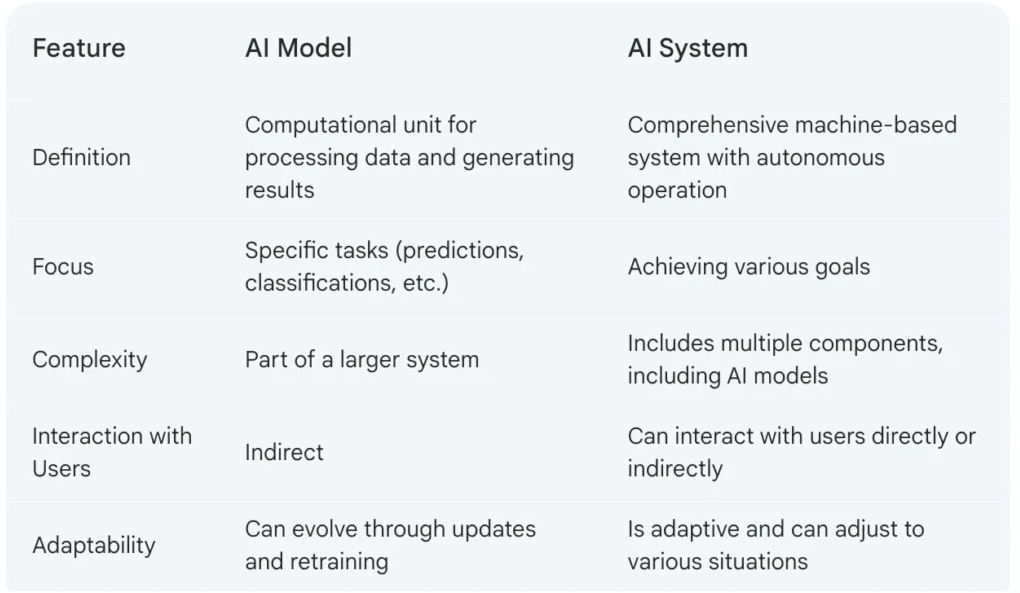

(1) Hochrisiko-KI-Systeme, in denen Techniken eingesetzt werden, bei denen KI-Modelle mit Daten trainiert werden, müssen mit Trainings-, Validierungs- und Testdatensätzen entwickelt werden, die den in den Absätzen 2 bis 5 genannten Qualitätskriterien entsprechen, wenn solche Datensätze verwendet werden.

(2) Für Trainings-, Validierungs- und Testdatensätze gelten Daten-Governance- und Datenverwaltungsverfahren, die für die Zweckbestimmung des Hochrisiko-KI-Systems geeignet sind. Diese Verfahren betreffen insbesondere

a) die einschlägigen konzeptionellen Entscheidungen,

b) die Datenerhebungsverfahren und die Herkunft der Daten und im Falle personenbezogener Daten den ursprünglichen Zweck der Datenerhebung,

c) relevante Datenaufbereitungsvorgänge wie Annotation, Kennzeichnung, Bereinigung, Aktualisierung, Anreicherung und Aggregierung,

d) die Aufstellung von Annahmen, insbesondere in Bezug auf die Informationen, die mit den Daten erfasst und dargestellt werden sollen,

e) eine Bewertung der Verfügbarkeit, Menge und Eignung der benötigten Datensätze,

f) eine Untersuchung im Hinblick auf mögliche Verzerrungen (Bias), die die Gesundheit und Sicherheit von Personen beeinträchtigen, sich negativ auf die Grundrechte auswirken oder zu einer nach den Rechtsvorschriften der Union verbotenen Diskriminierung führen könnten, insbesondere wenn die Datenausgaben die Eingaben für künftige Operationen beeinflussen,

g) geeignete Maßnahmen zur Erkennung, Verhinderung und Abschwächung möglicher gemäß Buchstabe f ermittelter Verzerrungen,

h) die Ermittlung relevanter Datenlücken oder Mängel, die der Einhaltung dieser Verordnung entgegenstehen, und wie diese Lücken und Mängel behoben werden können.

(3) Die Trainings-, Validierungs- und Testdatensätze müssen im Hinblick auf die Zweckbestimmung relevant, hinreichend repräsentativ und so weit wie möglich fehlerfrei und vollständig sein. Sie müssen die geeigneten statistischen Merkmale, gegebenenfalls auch bezüglich der Personen oder Personengruppen, für die das Hochrisiko-KI-System bestimmungsgemäß verwendet werden soll, haben. Diese Merkmale der Datensätze können auf der Ebene einzelner Datensätze oder auf der Ebene einer Kombination davon erfüllt werden.

(4) Die Datensätze müssen, soweit dies für die Zweckbestimmung erforderlich ist, die entsprechenden Merkmale oder Elemente berücksichtigen, die für die besonderen geografischen, kontextuellen, verhaltensbezogenen oder funktionalen Rahmenbedingungen, unter denen das Hochrisiko-KI-System bestimmungsgemäß verwendet werden soll, typisch sind.

(5) Soweit dies für die Erkennung und Korrektur von Verzerrungen im Zusammenhang mit Hochrisiko-KI-Systemen im Einklang mit Absatz 2 Buchstaben f und g dieses Artikels unbedingt erforderlich ist, dürfen die Anbieter solcher Systeme ausnahmsweise besondere Kategorien personenbezogener Daten verarbeiten, wobei sie angemessene Vorkehrungen für den Schutz der Grundrechte und Grundfreiheiten natürlicher Personen treffen müssen. Zusätzlich zu den Bestimmungen der Verordnungen (EU) 2016/679 und (EU) 2018/1725 und der Richtlinie (EU) 2016/680 müssen alle folgenden Bedingungen erfüllt sein, damit eine solche Verarbeitung stattfinden kann:

a) Die Erkennung und Korrektur von Verzerrungen kann durch die Verarbeitung anderer Daten, einschließlich synthetischer oder anonymisierter Daten, nicht effektiv durchgeführt werden;

b) die besonderen Kategorien personenbezogener Daten unterliegen technischen Beschränkungen einer Weiterverwendung der personenbezogenen Daten und modernsten Sicherheits- und Datenschutzmaßnahmen, einschließlich Pseudonymisierung;

c) die besonderen Kategorien personenbezogener Daten unterliegen Maßnahmen, mit denen sichergestellt wird, dass die verarbeiteten personenbezogenen Daten gesichert, geschützt und Gegenstand angemessener Sicherheitsvorkehrungen sind, wozu auch strenge Kontrollen des Zugriffs und seine Dokumentation gehören, um Missbrauch zu verhindern und sicherzustellen, dass nur befugte Personen Zugang zu diesen personenbezogenen Daten mit angemessenen Vertraulichkeitspflichten haben;

d) die besonderen Kategorien personenbezogener Daten werden nicht an Dritte übermittelt oder übertragen, noch haben diese Dritten anderweitigen Zugang zu diesen Daten;

e) die besonderen Kategorien personenbezogener Daten werden gelöscht, sobald die Verzerrung korrigiert wurde oder das Ende der Speicherfrist für die personenbezogenen Daten erreicht ist, je nachdem, was zuerst eintritt;

f) die Aufzeichnungen über Verarbeitungstätigkeiten gemäß den Verordnungen (EU) 2016/679 und (EU) 2018/1725 und der Richtlinie (EU) 2016/680 enthalten die Gründe, warum die Verarbeitung besonderer Kategorien personenbezogener Daten für die Erkennung und Korrektur von Verzerrungen unbedingt erforderlich war und warum dieses Ziel mit der Verarbeitung anderer Daten nicht erreicht werden konnte.

(6) Bei der Entwicklung von Hochrisiko-KI-Systemen, in denen keine Techniken eingesetzt werden, bei denen KI-Modelle trainiert werden, gelten die Absätze 2 bis 5 nur für Testdatensätze.

Artikel 50

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Transparenzpflichten für Anbieter und Betreiber bestimmter KI-Systeme

(1) Die Anbieter stellen sicher, dass KI-Systeme, die für die direkte Interaktion mit natürlichen Personen bestimmt sind, so konzipiert und entwickelt werden, dass die betreffenden natürlichen Personen informiert werden, dass sie mit einem KI-System interagieren, es sei denn, dies ist aus Sicht einer angemessen informierten, aufmerksamen und verständigen natürlichen Person aufgrund der Umstände und des Kontexts der Nutzung offensichtlich. Diese Pflicht gilt nicht für gesetzlich zur Aufdeckung, Verhütung, Ermittlung oder Verfolgung von Straftaten zugelassene KI-Systeme, wenn geeignete Schutzvorkehrungen für die Rechte und Freiheiten Dritter bestehen, es sei denn, diese Systeme stehen der Öffentlichkeit zur Anzeige einer Straftat zur Verfügung.

(2) Anbieter von KI-Systemen, einschließlich KI-Systemen mit allgemeinem Verwendungszweck, die synthetische Audio-, Bild-, Video- oder Textinhalte erzeugen, stellen sicher, dass die Ausgaben des KI-Systems in einem maschinenlesbaren Format gekennzeichnet und als künstlich erzeugt oder manipuliert erkennbar sind. Die Anbieter sorgen dafür, dass — soweit technisch möglich — ihre technischen Lösungen wirksam, interoperabel, belastbar und zuverlässig sind und berücksichtigen dabei die Besonderheiten und Beschränkungen der verschiedenen Arten von Inhalten, die Umsetzungskosten und den allgemein anerkannten Stand der Technik, wie er in den einschlägigen technischen Normen zum Ausdruck kommen kann. Diese Pflicht gilt nicht, soweit die KI-Systeme eine unterstützende Funktion für die Standardbearbeitung ausführen oder die vom Betreiber bereitgestellten Eingabedaten oder deren Semantik nicht wesentlich verändern oder wenn sie zur Aufdeckung, Verhütung, Ermittlung oder Verfolgung von Straftaten gesetzlich zugelassen sind.

(3) Die Betreiber eines Emotionserkennungssystems oder eines Systems zur biometrischen Kategorisierung informieren die davon betroffenen natürlichen Personen über den Betrieb des Systems und verarbeiten personenbezogene Daten gemäß den Verordnungen (EU) 2016/679 und (EU) 2018/1725 und der Richtlinie (EU) 2016/680. Diese Pflicht gilt nicht für gesetzlich zur Aufdeckung, Verhütung oder Ermittlung von Straftaten zugelassene KI-Systeme, die zur biometrischen Kategorisierung und Emotionserkennung im Einklang mit dem Unionsrecht verwendet werden, sofern geeignete Schutzvorkehrungen für die Rechte und Freiheiten Dritter bestehen.

(4) Betreiber eines KI-Systems, das Bild-, Ton- oder Videoinhalte erzeugt oder manipuliert, die ein Deepfake sind, müssen offenlegen, dass die Inhalte künstlich erzeugt oder manipuliert wurden. Diese Pflicht gilt nicht, wenn die Verwendung zur Aufdeckung, Verhütung, Ermittlung oder Verfolgung von Straftaten gesetzlich zugelassen ist. Ist der Inhalt Teil eines offensichtlich künstlerischen, kreativen, satirischen, fiktionalen oder analogen Werks oder Programms, so beschränken sich die in diesem Absatz festgelegten Transparenzpflichten darauf, das Vorhandensein solcher erzeugten oder manipulierten Inhalte in geeigneter Weise offenzulegen, die die Darstellung oder den Genuss des Werks nicht beeinträchtigt.

Betreiber eines KI-Systems, das Text erzeugt oder manipuliert, der veröffentlicht wird, um die Öffentlichkeit über Angelegenheiten von öffentlichem Interesse zu informieren, müssen offenlegen, dass der Text künstlich erzeugt oder manipuliert wurde. Diese Pflicht gilt nicht, wenn die Verwendung zur Aufdeckung, Verhütung, Ermittlung oder Verfolgung von Straftaten gesetzlich zugelassen ist oder wenn die durch KI erzeugten Inhalte einem Verfahren der menschlichen Überprüfung oder redaktionellen Kontrolle unterzogen wurden und wenn eine natürliche oder juristische Person die redaktionelle Verantwortung für die Veröffentlichung der Inhalte trägt.

(5) Die in den Absätzen 1 bis 4 genannten Informationen werden den betreffenden natürlichen Personen spätestens zum Zeitpunkt der ersten Interaktion oder Aussetzung in klarer und eindeutiger Weise bereitgestellt. Die Informationen müssen den geltenden Barrierefreiheitsanforderungen entsprechen.

(6) Die Absätze 1 bis 4 lassen die in Kapitel III festgelegten Anforderungen und Pflichten unberührt und berühren nicht andere Transparenzpflichten, die im Unionsrecht oder dem nationalen Recht für Betreiber von KI-Systemen festgelegt sind.

(7) Das Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz fördert und erleichtert die Ausarbeitung von Praxisleitfäden auf Unionsebene, um die wirksame Umsetzung der Pflichten in Bezug auf die Feststellung und Kennzeichnung künstlich erzeugter oder manipulierter Inhalte zu erleichtern. Die Kommission kann Durchführungsrechtsakte zur Genehmigung dieser Praxisleitfäden nach dem in Artikel 56 Absatz 6 festgelegten Verfahren erlassen. Hält sie einen Kodex für nicht angemessen, so kann die Kommission einen Durchführungsrechtsakt gemäß dem in Artikel 98 Absatz 2 genannten Prüfverfahren erlassen, in dem gemeinsame Vorschriften für die Umsetzung dieser Pflichten festgelegt werden.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 57

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

KI-Reallabore

(1) Die Mitgliedstaaten sorgen dafür, dass ihre zuständigen Behörden mindestens ein KI-Reallabor auf nationaler Ebene einrichten, das bis zum 2. August 2026 einsatzbereit sein muss. Dieses Reallabor kann auch gemeinsam mit den zuständigen Behörden anderer Mitgliedstaaten eingerichtet werden. Die Kommission kann technische Unterstützung, Beratung und Instrumente für die Einrichtung und den Betrieb von KI-Reallaboren bereitstellen.

Die Verpflichtung nach Unterabsatz 1 kann auch durch Beteiligung an einem bestehenden Reallabor erfüllt werden, sofern eine solche Beteiligung die nationale Abdeckung der teilnehmenden Mitgliedstaaten in gleichwertigem Maße gewährleistet.

(2) Es können auch zusätzliche KI-Reallabore auf regionaler oder lokaler Ebene oder gemeinsam mit den zuständigen Behörden anderer Mitgliedstaaten eingerichtet werden;

(3) Der Europäische Datenschutzbeauftragte kann auch ein KI-Reallabor für Organe, Einrichtungen und sonstige Stellen der Union einrichten und die Rollen und Aufgaben der zuständigen nationalen Behörden im Einklang mit diesem Kapitel wahrnehmen.

(4) Die Mitgliedstaaten stellen sicher, dass die in den Absätzen 1 und 2 genannten zuständigen Behörden ausreichende Mittel bereitstellen, um diesem Artikel wirksam und zeitnah nachzukommen. Gegebenenfalls arbeiten die zuständigen nationalen Behörden mit anderen einschlägigen Behörden zusammen und können die Einbeziehung anderer Akteure des KI-Ökosystems gestatten. Andere Reallabore, die im Rahmen des Unionsrechts oder des nationalen Rechts eingerichtet wurden, bleiben von diesem Artikel unberührt. Die Mitgliedstaaten sorgen dafür, dass die diese anderen Reallabore beaufsichtigenden Behörden und die zuständigen nationalen Behörden angemessen zusammenarbeiten.

(5) Die nach Absatz 1 eingerichteten KI-Reallabore bieten eine kontrollierte Umgebung, um Innovation zu fördern und die Entwicklung, das Training, das Testen und die Validierung innovativer KI-Systeme für einen begrenzten Zeitraum vor ihrem Inverkehrbringen oder ihrer Inbetriebnahme nach einem bestimmten zwischen den Anbietern oder zukünftigen Anbietern und der zuständigen Behörde vereinbarten Reallabor-Plan zu erleichtern. In diesen Reallaboren können auch darin beaufsichtigte Tests unter Realbedingungen durchgeführt werden.

(6) Die zuständigen Behörden stellen innerhalb der KI-Reallabore gegebenenfalls Anleitung, Aufsicht und Unterstützung bereit, um Risiken, insbesondere im Hinblick auf Grundrechte, Gesundheit und Sicherheit, Tests und Risikominderungsmaßnahmen sowie deren Wirksamkeit hinsichtlich der Pflichten und Anforderungen dieser Verordnung und gegebenenfalls anderem Unionsrecht und nationalem Recht, deren Einhaltung innerhalb des Reallabors beaufsichtigt wird, zu ermitteln.

(7) Die zuständigen Behörden stellen den Anbietern und zukünftigen Anbietern, die am KI-Reallabor teilnehmen, Leitfäden zu regulatorischen Erwartungen und zur Erfüllung der in dieser Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen und Pflichten zur Verfügung.

Die zuständige Behörde legt dem Anbieter oder zukünftigen Anbieter des KI-Systems auf dessen Anfrage einen schriftlichen Nachweis für die im Reallabor erfolgreich durchgeführten Tätigkeiten vor. Außerdem legt die zuständige Behörde einen Abschlussbericht vor, in dem sie die im Reallabor durchgeführten Tätigkeiten, deren Ergebnisse und die gewonnenen Erkenntnisse im Einzelnen darlegt. Die Anbieter können diese Unterlagen nutzen, um im Rahmen des Konformitätsbewertungsverfahrens oder einschlägiger Marktüberwachungstätigkeiten nachzuweisen, dass sie dieser Verordnung nachkommen. In diesem Zusammenhang werden die Abschlussberichte und die von der zuständigen nationalen Behörde vorgelegten schriftlichen Nachweise von den Marktüberwachungsbehörden und den notifizierten Stellen im Hinblick auf eine Beschleunigung der Konformitätsbewertungsverfahren in angemessenem Maße positiv gewertet.

(8) Vorbehaltlich der in Artikel 78 enthaltenen Bestimmungen über die Vertraulichkeit und im Einvernehmen mit den Anbietern oder zukünftigen Anbietern, sind die Kommission und das KI-Gremium befugt, die Abschlussberichte einzusehen und tragen diesen gegebenenfalls bei der Wahrnehmung ihrer Aufgaben gemäß dieser Verordnung Rechnung. Wenn der Anbieter oder der zukünftige Anbieter und die zuständige nationale Behörde ihr ausdrückliches Einverständnis erklären, kann der Abschlussbericht über die in diesem Artikel genannte zentrale Informationsplattform veröffentlicht werden.

(9) Die Einrichtung von KI-Reallaboren soll zu den folgenden Zielen beitragen:

a) Verbesserung der Rechtssicherheit, um für die Einhaltung der Regulierungsvorschriften dieser Verordnung oder, gegebenenfalls, anderem geltenden Unionsrecht und nationalem Recht zu sorgen;

b) Förderung des Austauschs bewährter Verfahren durch Zusammenarbeit mit den am KI-Reallabor beteiligten Behörden;

c) Förderung von Innovation und Wettbewerbsfähigkeit sowie Erleichterung der Entwicklung eines KI-Ökosystems;

d) Leisten eines Beitrags zum evidenzbasierten regulatorischen Lernen;

e) Erleichterung und Beschleunigung des Zugangs von KI-Systemen zum Unionsmarkt, insbesondere wenn sie von KMU — einschließlich Start-up-Unternehmen — angeboten werden.

(10) Soweit die innovativen KI-Systeme personenbezogene Daten verarbeiten oder anderweitig der Aufsicht anderer nationaler Behörden oder zuständiger Behörden unterstehen, die den Zugang zu personenbezogenen Daten gewähren oder unterstützen, sorgen die zuständigen nationalen Behörden dafür, dass die nationalen Datenschutzbehörden oder diese anderen nationalen oder zuständigen Behörden in den Betrieb des KI-Reallabors sowie in die Überwachung dieser Aspekte im vollen Umfang ihrer entsprechenden Aufgaben und Befugnisse einbezogen werden.

(11) Die KI-Reallabore lassen die Aufsichts- oder Abhilfebefugnisse der die Reallabore beaufsichtigenden zuständigen Behörden, einschließlich auf regionaler oder lokaler Ebene, unberührt. Alle erheblichen Risiken für die Gesundheit und Sicherheit und die Grundrechte, die bei der Entwicklung und Erprobung solcher KI-Systeme festgestellt werden, führen zur sofortigen und angemessenen Risikominderung. Die zuständigen nationalen Behörden sind befugt, das Testverfahren oder die Beteiligung am Reallabor vorübergehend oder dauerhaft auszusetzen, wenn keine wirksame Risikominderung möglich ist, und unterrichten das Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz über diese Entscheidung. Um Innovationen im Bereich KI in der Union zu fördern, üben die zuständigen nationalen Behörden ihre Aufsichtsbefugnisse im Rahmen des geltenden Rechts aus, indem sie bei der Anwendung der Rechtsvorschriften auf ein bestimmtes KI-Reallabor ihren Ermessensspielraum nutzen.

(12) Die am KI-Reallabor beteiligten Anbieter und zukünftigen Anbieter bleiben nach geltendem Recht der Union und nationalem Haftungsrecht für Schäden haftbar, die Dritten infolge der Erprobung im Reallabor entstehen. Sofern die zukünftigen Anbieter den spezifischen Plan und die Bedingungen für ihre Beteiligung beachten und der Anleitung durch die zuständigen nationalen Behörden in gutem Glauben folgen, werden jedoch von den Behörden keine Geldbußen für Verstöße gegen diese Verordnung verhängt. In Fällen, in denen andere zuständige Behörden, die für anderes Unionsrecht und nationales Recht zuständig sind, aktiv an der Beaufsichtigung des KI-Systems im Reallabor beteiligt waren und Anleitung für die Einhaltung gegeben haben, werden im Hinblick auf dieses Recht keine Geldbußen verhängt.

(13) Die KI-Reallabore sind so konzipiert und werden so umgesetzt, dass sie gegebenenfalls die grenzüberschreitende Zusammenarbeit zwischen zuständigen nationalen Behörden erleichtern.

(14) Die zuständigen nationalen Behörden koordinieren ihre Tätigkeiten und arbeiten im Rahmen des KI-Gremiums zusammen.

(15) Die zuständigen nationalen Behörden unterrichten das Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz und das KI-Gremium über die Einrichtung eines Reallabors und können sie um Unterstützung und Anleitung bitten. Das Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz veröffentlicht eine Liste der geplanten und bestehenden Reallabore und hält sie auf dem neuesten Stand, um eine stärkere Interaktion in den KI-Reallaboren und die grenzüberschreitende Zusammenarbeit zu fördern.

(16) Die zuständigen nationalen Behörden übermitteln dem Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz und dem KI-Gremium jährliche Berichte, und zwar ab einem Jahr nach der Einrichtung des Reallabors und dann jedes Jahr bis zu dessen Beendigung, sowie einen Abschlussbericht. Diese Berichte informieren über den Fortschritt und die Ergebnisse der Umsetzung dieser Reallabore, einschließlich bewährter Verfahren, Vorfällen, gewonnener Erkenntnisse und Empfehlungen zu deren Aufbau, sowie gegebenenfalls über die Anwendung und mögliche Überarbeitung dieser Verordnung, einschließlich ihrer delegierten Rechtsakte und Durchführungsrechtsakte, sowie über die Anwendung anderen Unionsrechts, deren Einhaltung von den zuständigen Behörden innerhalb des Reallabors beaufsichtigt wird. Die zuständigen nationalen Behörden stellen diese jährlichen Berichte oder Zusammenfassungen davon der Öffentlichkeit online zur Verfügung. Die Kommission trägt den jährlichen Berichten gegebenenfalls bei der Wahrnehmung ihrer Aufgaben gemäß dieser Verordnung Rechnung.

(17) Die Kommission richtet eine eigene Schnittstelle ein, die alle relevanten Informationen zu den KI-Reallaboren enthält, um es den Interessenträgern zu ermöglichen, mit den KI-Reallaboren zu interagieren und Anfragen an die zuständigen Behörden zu richten und unverbindliche Beratung zur Konformität von innovativen Produkten, Dienstleistungen und Geschäftsmodellen mit integrierter KI-Technologie im Einklang mit Artikel 62 Absatz 1 Buchstabe c einzuholen. Die Kommission stimmt sich gegebenenfalls proaktiv mit den zuständigen nationalen Behörden ab.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 59

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Weiterverarbeitung personenbezogener Daten zur Entwicklung bestimmter KI-Systeme im öffentlichen Interesse im KI-Reallabor

(1) Rechtmäßig für andere Zwecke erhobene personenbezogene Daten dürfen im KI-Reallabor ausschließlich für die Zwecke der Entwicklung, des Trainings und des Testens bestimmter KI-Systeme im Reallabor verarbeitet werden, wenn alle der folgenden Bedingungen erfüllt sind:

a) Die KI-Systeme werden zur Wahrung eines erheblichen öffentlichen Interesses durch eine Behörde oder eine andere natürliche oder juristische Person und in einem oder mehreren der folgenden Bereiche entwickelt:

i) öffentliche Sicherheit und öffentliche Gesundheit, einschließlich Erkennung, Diagnose, Verhütung, Bekämpfung und Behandlung von Krankheiten sowie Verbesserung von Gesundheitsversorgungssystemen;

ii) hohes Umweltschutzniveau und Verbesserung der Umweltqualität, Schutz der biologischen Vielfalt, Schutz gegen Umweltverschmutzung, Maßnahmen für den grünen Wandel sowie Klimaschutz und Anpassung an den Klimawandel;

iii) nachhaltige Energie;

iv) Sicherheit und Widerstandsfähigkeit von Verkehrssystemen und Mobilität, kritischen Infrastrukturen und Netzen;

v) Effizienz und Qualität der öffentlichen Verwaltung und öffentlicher Dienste;

b) die verarbeiteten Daten sind für die Erfüllung einer oder mehrerer der in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 genannten Anforderungen erforderlich, sofern diese Anforderungen durch die Verarbeitung anonymisierter, synthetischer oder sonstiger nicht personenbezogener Daten nicht wirksam erfüllt werden können;

c) es bestehen wirksame Überwachungsmechanismen, mit deren Hilfe festgestellt wird, ob während der Reallaborversuche hohe Risiken für die Rechte und Freiheiten betroffener Personen gemäß Artikel 35 der Verordnung (EU) 2016/679 und gemäß Artikel 39 der Verordnung (EU) 2018/1725 auftreten können, sowie Reaktionsmechanismen, mit deren Hilfe diese Risiken umgehend eingedämmt werden können und die Verarbeitung bei Bedarf beendet werden kann;

d) personenbezogene Daten, die im Rahmen des Reallabors verarbeitet werden sollen, befinden sich in einer funktional getrennten, isolierten und geschützten Datenverarbeitungsumgebung unter der Kontrolle des zukünftigen Anbieters, und nur befugte Personen haben Zugriff auf diese Daten;

e) Anbieter dürfen die ursprünglich erhobenen Daten nur im Einklang mit dem Datenschutzrecht der Union weitergeben; personenbezogene Daten, die im Reallabor erstellt wurden, dürfen nicht außerhalb des Reallabors weitergegeben werden;

f) eine Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten im Rahmen des Reallabors führt zu keinen Maßnahmen oder Entscheidungen, die Auswirkungen auf die betroffenen Personen haben, und berührt nicht die Anwendung ihrer Rechte, die in den Rechtsvorschriften der Union über den Schutz personenbezogener Daten festgelegt sind;

g) im Rahmen des Reallabors verarbeitete personenbezogene Daten sind durch geeignete technische und organisatorische Maßnahmen geschützt und werden gelöscht, sobald die Beteiligung an dem Reallabor endet oder das Ende der Speicherfrist für die personenbezogenen Daten erreicht ist;

h) die Protokolle der Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten im Rahmen des Reallabors werden für die Dauer der Beteiligung am Reallabor aufbewahrt, es sei denn, im Unionsrecht oder nationalen Recht ist etwas anderes bestimmt;

i) eine vollständige und detaillierte Beschreibung des Prozesses und der Gründe für das Trainieren, Testen und Validieren des KI-Systems wird zusammen mit den Testergebnissen als Teil der technischen Dokumentation gemäß Anhang IV aufbewahrt;

j) eine kurze Zusammenfassung des im Reallabor entwickelten KI-Projekts, seiner Ziele und der erwarteten Ergebnisse wird auf der Website der zuständigen Behörden veröffentlicht; diese Pflicht erstreckt sich nicht auf sensible operative Daten zu den Tätigkeiten von Strafverfolgungs-, Grenzschutz-, Einwanderungs- oder Asylbehörden.

(2) Für die Zwecke der Verhütung, Ermittlung, Aufdeckung oder Verfolgung von Straftaten oder der Strafvollstreckung — einschließlich des Schutzes vor und der Abwehr von Gefahren für die öffentliche Sicherheit — unter der Kontrolle und Verantwortung der Strafverfolgungsbehörden erfolgt die Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten in KI-Reallaboren auf der Grundlage eines spezifischen Unionsrechts oder nationalen Rechts und unterliegt den kumulativen Bedingungen des Absatzes 1.

(3) Das Unionsrecht oder nationale Recht, das die Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten für andere Zwecke als die ausdrücklich in jenem Recht genannten ausschließt, sowie Unionsrecht oder nationales Recht, in dem die Grundlagen für eine für die Zwecke der Entwicklung, des Testens oder des Trainings innovativer KI-Systeme notwendige Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten festgelegt sind, oder jegliche anderen dem Unionsrecht zum Schutz personenbezogener Daten entsprechenden Rechtsgrundlagen bleiben von Absatz 1 unberührt.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 102

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Verordnung (EG) Nr. 300/2008

In Artikel 4 Absatz 3 der Verordnung (EG) Nr. 300/2008 wird folgender Unterabsatz angefügt:

„Beim Erlass detaillierter Maßnahmen, die technische Spezifikationen und Verfahren für die Genehmigung und den Einsatz von Sicherheitsausrüstung betreffen, bei der auch Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates zum Einsatz kommen, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt. Artikel 103 Änderung der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 167/2013

In Artikel 17 Absatz 5 der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 167/2013 wird folgender Unterabsatz angefügt: „Beim Erlass delegierter Rechtsakte nach Unterabsatz 1, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 103

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 167/2013

In Artikel 4 Absatz 3 der Verordnung (EG) Nr. 300/2008 wird folgender Unterabsatz angefügt:

„Beim Erlass detaillierter Maßnahmen, die technische Spezifikationen und Verfahren für die Genehmigung und den Einsatz von Sicherheitsausrüstung betreffen, bei der auch Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates (1) zum Einsatz kommen, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt. Artikel 103 Änderung der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 167/2013

In Artikel 17 Absatz 5 der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 167/2013 wird folgender Unterabsatz angefügt: „Beim Erlass delegierter Rechtsakte nach Unterabsatz 1, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates (*2) handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 104

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 168/2013

In Artikel 22 Absatz 5 der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 168/2013 wird folgender Unterabsatz angefügt:

„Beim Erlass delegierter Rechtsakte nach Unterabsatz 1, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt. Artikel 105 Änderung der Richtlinie 2014/90/EU

In Artikel 8 der Richtlinie 2014/90/EU wird folgender Absatz angefügt: „(5) Bei Systemen der künstlichen Intelligenz, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, berücksichtigt die Kommission bei der Ausübung ihrer Tätigkeiten nach Absatz 1 und bei Erlass technischer Spezifikationen und Prüfnormen nach den Absätzen 2 und 3 die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 105

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Richtlinie 2014/90/EU

In Artikel 8 der Richtlinie 2014/90/EU wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(5) Bei Systemen der künstlichen Intelligenz, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, berücksichtigt die Kommission bei der Ausübung ihrer Tätigkeiten nach Absatz 1 und bei Erlass technischer Spezifikationen und Prüfnormen nach den Absätzen 2 und 3 die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 106

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Richtlinie (EU) 2016/797

In Artikel 5 der Richtlinie (EU) 2016/797 wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(12) Beim Erlass von delegierten Rechtsakten nach Absatz 1 und von Durchführungsrechtsakten nach Absatz 11, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 107

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Verordnung (EU) 2018/858

„(4) Beim Erlass delegierter Rechtsakte nach Absatz 3, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 108

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Verordnung (EU) 2018/1139

Die Verordnung (EU) 2018/113 wird wie folgt geändert:

- In Artikel 17 wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(3) Unbeschadet des Absatzes 2 werden beim Erlass von Durchführungsrechtsakten nach Absatz 1, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt. (7) Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 13. Juni 2024 zur Festlegung harmonisierter Vorschriften für künstliche Intelligenz und zur Änderung der Verordnungen (EG) Nr. 300/2008, (EU) Nr. 167/2013, (EU) Nr. 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 und (EU) 2019/2144 sowie der Richtlinien 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 und (EU) 2020/1828 (Verordnung über künstliche Intelligenz) (ABl. L, 2024/1689, 12.7.2024, ELI: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj).“ “

- In Artikel 19 wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(4) Beim Erlass delegierter Rechtsakte nach den Absätzen 1 und 2, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.“

- In Artikel 43 wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(4) Beim Erlass von Durchführungsrechtsakten nach Absatz 1, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.“

- In Artikel 47 wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(3) Beim Erlass delegierter Rechtsakte nach den Absätzen 1 und 2, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.“

- In Artikel 57 wird folgender Unterabsatz angefügt:

„Beim Erlass solcher Durchführungsrechtsakte, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.“

- In Artikel 58 wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(3) Beim Erlass delegierter Rechtsakte nach den Absätzen 1 und 2, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.“

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 109

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Änderung der Richtlinie (EU) 2019/2144

In Artikel 11 der Verordnung (EU) 2019/2144 wird folgender Absatz angefügt:

„(3) Beim Erlass von Durchführungsrechtsakten nach Absatz 2, die sich auf Systeme der künstlichen Intelligenz beziehen, bei denen es sich um Sicherheitsbauteile im Sinne der Verordnung (EU) 2024/1689 des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates handelt, werden die in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 jener Verordnung festgelegten Anforderungen berücksichtigt.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Artikel 112

Lesedauer 16 Minuten

Bewertung und Überprüfung

(1) Die Kommission prüft nach Inkrafttreten dieser Verordnung und bis zum Ende der Befugnisübertragung gemäß Artikel 97 einmal jährlich, ob eine Änderung der Liste in Anhang III und der Liste der verbotenen Praktiken im KI-Bereich gemäß Artikel 5 erforderlich ist. Die Kommission übermittelt die Ergebnisse dieser Bewertung dem Europäischen Parlament und dem Rat.

(2) Bis zum 2. August 2028 und danach alle vier Jahre bewertet die Kommission Folgendes und erstattet dem Europäischen Parlament und dem Rat Bericht darüber:

a) Notwendigkeit von Änderungen zur Erweiterung bestehender Bereiche oder zur Aufnahme neuer Bereiche in Anhang III:

b) Änderungen der Liste der KI-Systeme, die zusätzliche Transparenzmaßnahmen erfordern, in Artikel 50;

c) Änderungen zur Verbesserung der Wirksamkeit des Überwachungs- und Governance-Systems.

(3) Bis zum 2. August 2029 und danach alle vier Jahre legt die Kommission dem Europäischen Parlament und dem Rat einen Bericht über die Bewertung und Überprüfung dieser Verordnung vor. Der Bericht enthält eine Beurteilung hinsichtlich der Durchsetzungsstruktur und der etwaigen Notwendigkeit einer Agentur der Union zur Lösung der festgestellten Mängel. Auf der Grundlage der Ergebnisse wird diesem Bericht gegebenenfalls ein Vorschlag zur Änderung dieser Verordnung beigefügt. Die Berichte werden veröffentlicht.

(4) In den in Absatz 2 genannten Berichten wird insbesondere auf folgende Aspekte eingegangen:

a) Sachstand bezüglich der finanziellen, technischen und personellen Ressourcen der zuständigen nationalen Behörden im Hinblick auf deren Fähigkeit, die ihnen auf der Grundlage dieser Verordnung übertragenen Aufgaben wirksam zu erfüllen;

b) Stand der Sanktionen, insbesondere der Bußgelder nach Artikel 99 Absatz 1, die Mitgliedstaaten bei Verstößen gegen diese Verordnung verhängt haben;

c) angenommene harmonisierte Normen und gemeinsame Spezifikationen, die zur Unterstützung dieser Verordnung erarbeitet wurden;

d) Zahl der Unternehmen, die nach Inkrafttreten dieser Verordnung in den Markt eintreten, und wie viele davon KMU sind.

(5) Bis zum 2. August 2028 bewertet die Kommission die Arbeitsweise des Büros für Künstliche Intelligenz und prüft, ob das Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz mit ausreichenden Befugnissen und Zuständigkeiten zur Erfüllung seiner Aufgaben ausgestattet wurde, und ob es für die ordnungsgemäße Durchführung und Durchsetzung dieser Verordnung zweckmäßig und erforderlich wäre, das Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz und seine Durchsetzungskompetenzen zu erweitern und seine Ressourcen aufzustocken. Die Kommission übermittelt dem Europäischen Parlament und dem Rat einen Bericht über ihre Bewertung.

(6) Bis zum 2. August 2028 und danach alle vier Jahre legt die Kommission einen Bericht über die Überprüfung der Fortschritte bei der Entwicklung von Normungsdokumenten zur energieeffizienten Entwicklung von KI-Modellen mit allgemeinem Verwendungszweck vor und beurteilt die Notwendigkeit weiterer Maßnahmen oder Handlungen, einschließlich verbindlicher Maßnahmen oder Handlungen. Dieser Bericht wird dem Europäischen Parlament und dem Rat vorgelegt und veröffentlicht.

(7) Bis zum 2. August 2028 und danach alle drei Jahre führt die Kommission eine Bewertung der Folgen und der Wirksamkeit der freiwilligen Verhaltenskodizes durch, mit denen die Anwendung der in Kapitel III Abschnitt 2 festgelegten Anforderungen an andere KI-Systeme als Hochrisiko-KI-Systeme und möglicherweise auch zusätzlicher Anforderungen an andere KI-Systeme als Hochrisiko-KI-Systeme, auch in Bezug auf deren ökologische Nachhaltigkeit, gefördert werden soll.

(8) Für die Zwecke der Absätze 1 bis 7 übermitteln das KI-Gremium, die Mitgliedstaaten und die zuständigen nationalen Behörden der Kommission auf Anfrage unverzüglich die gewünschten Informationen.

(9) Bei den in den Absätzen 1 bis 7 genannten Bewertungen und Überprüfungen berücksichtigt die Kommission die Standpunkte und Feststellungen des KI-Gremiums, des Europäischen Parlaments, des Rates und anderer einschlägiger Stellen oder Quellen.

(10) Die Kommission legt erforderlichenfalls geeignete Vorschläge zur Änderung dieser Verordnung vor und berücksichtigt dabei insbesondere technologische Entwicklungen, die Auswirkungen von KI-Systemen auf die Gesundheit und Sicherheit und auf die Grundrechte und die Fortschritte in der Informationsgesellschaft.

(11) Als Orientierung für die in den Absätzen 1 bis 7 genannten Bewertungen und Überprüfungen entwickelt das Büro für Künstliche Intelligenz ein Ziel und eine partizipative Methode für die Bewertung der Risikoniveaus anhand der in den jeweiligen Artikeln genannten Kriterien und für die Einbeziehung neuer Systeme in

a) die Liste gemäß Anhang III, einschließlich der Erweiterung bestehender Bereiche oder der Aufnahme neuer Bereiche in diesen Anhang;

b) die Liste der verbotenen Praktiken gemäß Artikel 5; und

c) die Liste der KI-Systeme, die zusätzliche Transparenzmaßnahmen erfordern, in Artikel 50.

(12) Eine Änderung dieser Verordnung im Sinne des Absatzes 10 oder entsprechende delegierte Rechtsakte oder Durchführungsrechtsakte, die sektorspezifische Rechtsvorschriften für eine unionsweite Harmonisierung gemäß Anhang I Abschnitt B betreffen, berücksichtigen die regulatorischen Besonderheiten des jeweiligen Sektors und die in der Verordnung festgelegten bestehenden Governance-, Konformitätsbewertungs- und Durchsetzungsmechanismen und -behörden.

(13) Bis zum 2. August 2031 nimmt die Kommission unter Berücksichtigung der ersten Jahre der Anwendung der Verordnung eine Bewertung der Durchsetzung dieser Verordnung vor und erstattet dem Europäischen Parlament, dem Rat und dem Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss darüber Bericht. Auf Grundlage der Ergebnisse wird dem Bericht gegebenenfalls ein Vorschlag zur Änderung dieser Verordnung beigefügt, der die Struktur der Durchsetzung und die Notwendigkeit einer Agentur der Union für die Lösung festgestellter Mängel betrifft.

Finale Version vom 12. Juli 2024, siehe https://cair4.eu/eu-ai-act-2024-07-de

Be First to Comment